Last week, Andrej Karpathy released LLM Council.

If you don't know Karpathy: he built the AI that taught Tesla cars to drive themselves. Before that, he was a founding member of OpenAI. When he builds something, people pay attention.

His idea: ask multiple AI models the same question. Let them see each other's responses. Have them rank who did best. Then a "Chairman" AI synthesizes the final answer.

The project got thousands of stars in days. But what caught my attention was what he said about it:

"Models consistently praise GPT 5.1 as the best and most insightful model, and consistently select Claude as the worst... But I'm not 100% convinced this aligns with my own qualitative assessment."

The models ranked each other—but Karpathy's gut disagreed.

He added:

"The construction of LLM ensembles seems under-explored. There's probably a whole design space of the data flow of your LLM council."

That "design space" comment stuck with me. I've been building TachiBot, a multi-model tool for Claude Code, and it takes a completely different approach. I wanted to understand why.

Two Architectures for Multi-Model AI

When you ask multiple AIs the same question, what do you do with the answers?

LLM Council's approach: Peer Ranking

- All models answer the question

- Each model reviews the others: "Response A does well in... does poorly by..."

- Models rank each other from best to worst

- A Chairman synthesizes the best elements

TachiBot's approach: Peer Challenge

- Multiple models analyze the question

- Each model challenges the others: "Hidden assumptions... edge cases that break this..."

- Models find flaws and counter-evidence

- A consensus emerges from the debate

The difference is subtle but important:

- Ranking asks: "Which answer is best?"

- Challenging asks: "What's wrong with these answers?"

Both systems use critique—but LLM Council's critique serves the ranking, while TachiBot's critique is the process.

Think of it this way: LLM Council is a boardroom meeting—polite, balanced, reaching consensus. TachiBot is a courtroom cross-examination—adversarial, probing, breaking the witness, with Perplexity and Grok fact-checking claims against live web sources.

But which approach finds what you actually need?

What This Looks Like in Practice

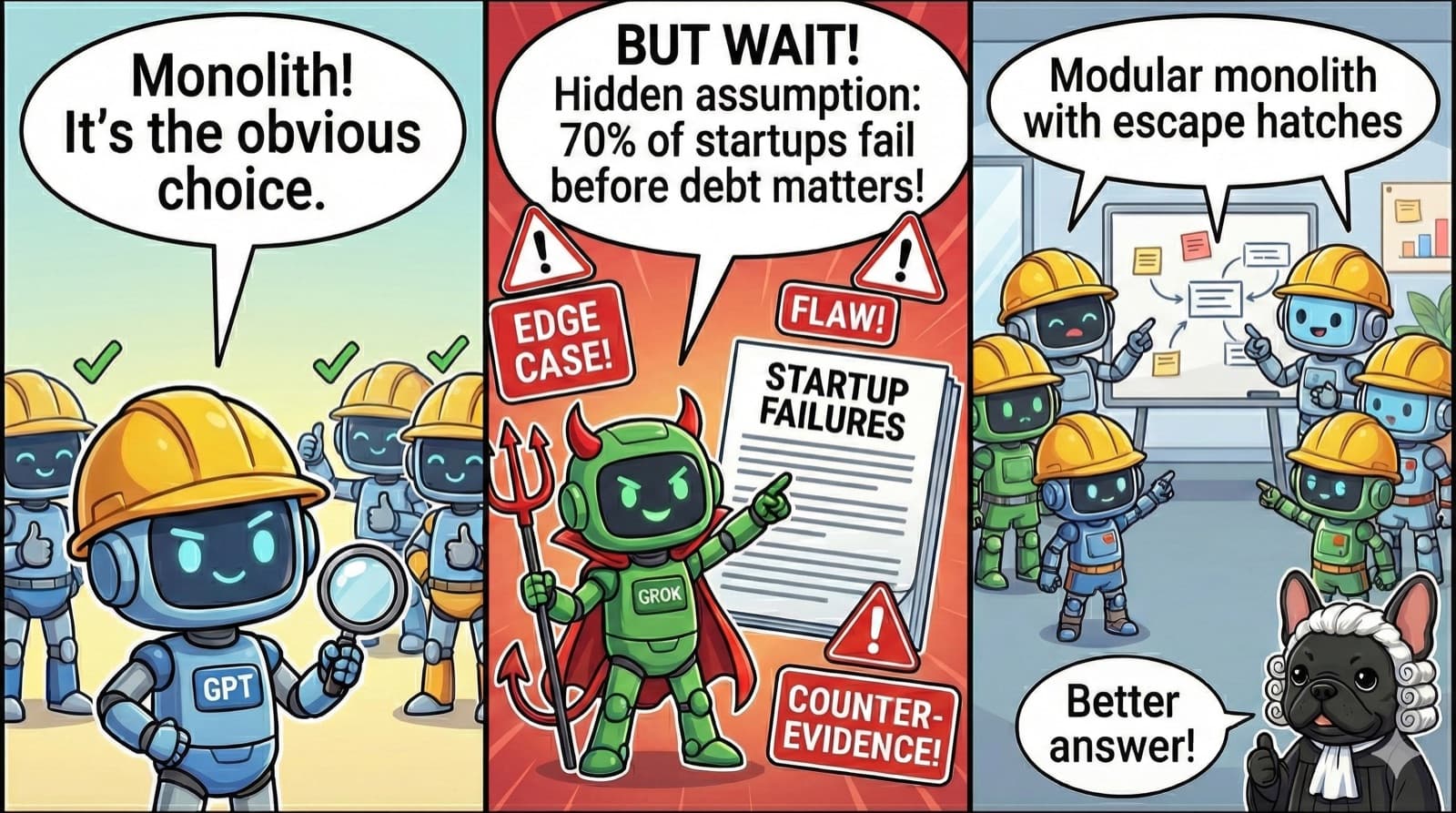

I asked both systems: "Should a startup build with microservices or a monolith?"

LLM Council's Output

The Chairman reviewed the rankings and synthesized:

"Monolith until proven guilty."

Clean. Memorable. The peer rankings noted which responses were comprehensive vs. terse, and the synthesis picked the best elements from each.

TachiBot's Output

The challenge step from Grok tore into the consensus:

"Cherry-picking and source homogeneity... This creates an echo chamber."

"Overemphasis on pro-monolith sources, downplaying counterarguments."

"Hidden assumption: Long-term project survival. Reality: 70-80% of startups fail within 2-5 years. Most codebases are abandoned before debt bites."

Then it listed edge cases: hyper-scale startups, distributed teams, compliance-heavy domains, AI/ML workloads.

The final consensus:

"Start with a modular monolith—one deployable app with clean internal boundaries—because it maximizes early speed while preserving escape hatches to spin out services when scale demands it."

Same Question, Different Discoveries

Both systems reached similar conclusions (monolith-first). But the journey was different.

LLM Council surfaced:

- Which models were most comprehensive

- Which answers were too terse or too verbose

- A well-synthesized soundbite

TachiBot surfaced:

- Hidden assumptions in the consensus

- Edge cases where the advice fails

- Counter-evidence the initial answers missed

Neither is "better." They're different tools for different purposes.

So when should you use which?

When Each Approach Shines

Ranking works well when:

- You need to filter out bad answers (hallucinations, errors)

- You want a polished, synthesized response

- The question has a "best" answer worth finding

Challenging works well when:

- The question involves tradeoffs with no clear winner

- You need to stress-test assumptions

- You want to find edge cases before committing

Karpathy noticed something similar. When his models ranked each other, they consistently picked GPT 5.1 as best—but he found it "too wordy." The ranking reflected majority preference, not necessarily what he needed.

Here's the uncomfortable question: What if the majority is wrong?

The Under-Explored Design Space

Karpathy called this "under-explored," and he's right.

Most multi-model systems default to consensus: average the answers, vote on the best, synthesize into one. The boardroom reaches agreement. That works for filtering noise.

But what if the minority opinion is the one you need? What if the consensus is missing a crucial edge case? Sometimes you need the courtroom—someone willing to break the witness. Ranking won't surface that. Challenging might.

The design space includes:

- Ranking (LLM Council): Who answered best?

- Challenging (TachiBot's pingpong): What's wrong with these answers?

- Specialization: Different models for different tasks (research, analysis, synthesis)

- Debate: Models argue opposing positions

- Verification: One model checks another's work

We're just scratching the surface.

Try It Yourself

LLM Council: github.com/karpathy/llm-council

Run your own questions through it. Watch how models rank each other. Notice when you agree with their ranking—and when you don't.

TachiBot: tachibot.com

Full disclosure: I built this. But the pingpong workflow that challenges answers is genuinely different from ranking. Try both—the boardroom and the courtroom—and see which surfaces insights you'd have missed.

Thanks to Karpathy for calling this space "under-explored." He's right—and that's what makes it interesting.